The Archaeology and History of Jerash - 110 years of excavations

Summary of the conference "The Archaeology and History of Jerash - 110 years of excavations" at the Royal Academy of Sciences and Letters, Copenhagen, 2-3 March 2017. Written by Research Assistant Eva Mortensen.

By Research Assistant Eva Mortensen.

In March, researchers convened at the Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters in Copenhagen for the two-day international conference ‘The Archaeology and History of Jerash – 110 Years of Excavations’ to discuss past years’ methods and results of excavations in Jerash, previous and on-going research as well as the future for archaeology in Jerash. Twenty-one speakers, who have been working in Jerash, gave presentations.

First day – 2 March 2017

Achim Lichtenberger (AL) & Rubina Raja (RR): Archaeological Research in Jerash and the Danish-German Northwest Quarter Project 2011–2016

AL opened this paper by giving an overview of the research history of Jerash. The rediscovery began with Ulrich Jasper Seetzen, who identified the place as Gerasa. With him he had a map made by Paulus in 1972 – on this map Gerasa is located on the northeastern side of the Sea of Galilee. The next turning point in the research history of Jerash was Gottlieb Schumacher, whose systematic archaeological observations on and descriptions of Jerash are highly important. Then in 1907 the first excavations were undertaken. Heinrich Kohl visited Jerash in 1907 and from his letters we know that he bought part of a mosaic that had been illicitly excavated. Some of the larger excavation projects in Jerash were introduced in the paper, and so was ‘early high definition archaeology’ in Jerash. Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin – the Nobel Prize winner in chemistry in 1964 – was the daughter of John Crowfoot who carried out excavations in Jerash, and she was the first to chemically investigate archaeological objects, namely glass tesserae, in Jerash.

RR continued the paper focusing on the Danish-German Northwest Quarter Project. In this project focus has shifted away from the large public monuments along the cardo to the urban periphery, and one of the main research questions was: How was this area integrated into the urban structure? The Northwest Quarter is quite far from the urban centre, and though many were a bit sceptical about what would be gained from investigating this big rubble field, many new insights into the settlement history of Jerash have been gained.

RR gave a short overview of some of the finds and the settlement history of the Northwest Quarter, she highlighted important questions that the material from the area gives rise to, and discussed some of this in further detail: questions of water management in the area are tackled on different levels in the project in order to clarify how the area was fed with water (since it was not fed with water from the Golden River). Various water installations from different periods have been found in the area (large cisterns, water channel systems, bootle-shaped cisterns in houses, and roof cisterns). Last year the project had the opportunity to buy LiDAR-data, and thus height differences in Jerash can be modelled very precisely (see lecture by SMK & ISi), offering a different way of investigating water management at the site; another important question relating to the infra structure of Jerash was answered by trenches on the north side of the Northwest Quarter revealing that the north decumanus did not extent all the way to the city wall. This was not a route taking people in and out of the city; whether the Northwest Quarter was in fact used as necropolis has been disproved by the lack of human bones, and RR argued that it is now time to end that discussion; in order to better understand the synagogue church and the changes it went through, excavations were carried out near the building, and a mosaic hall with two dated inscriptions (March 576 and July 591) were uncovered. In the inscriptions the Electi Justiniani (Justinian troops) are mentioned, and perhaps they had a connection with the synagogue changing into a church; on the east terrace of the area, parts of which were excavated in 2015 and 2016, an early Islamic complex that collapsed during the earthquake of AD 749 was found. Besides finding glass, tools for textile production, pearls, a coin hoard and a silver scroll, different stages of mosaic production was uncovered in the complex which at the time of the earthquake was undergoing restoration. Tesserae were made in the house and a skeleton (the only human bones found in the area) with a tool (for making tesserae?) may have been one of the workers.

In the discussion, the north decumanus and other ways of reaching the city wall was discussed further. There is no clear answer to whether another street led to the gate, and indeed there is no clear answer to whether a gate existed. No proper gate is seen there, so perhaps it was not completed. On the other hand, there is a necropolis on the other side, which does hint that a street system existed here. The topography of the ‘northern edge’ of the Northwest Quarter is very different today than it was in antiquity, which makes it difficult to say more about a possible street here. Also a gem found in a cistern was discussed further. The magical Greek text on the backside (which would not have been seen when the ring was worn), cannot be read, and Richard Gordon has concluded that it is nonsense. It was made of hematite, but unfortunately it is too small to do examinations on. The discussion then turned to the synagogue and its conversion into a church. Do the mosaics of the synagogue church tell us that Jews converted into Christians, or do the newly revealed mosaics of the neighbouring ecclesiastic complex related to the military instead reveal that Justinian took the building from the Jews and made it into a church for his men? Last but not least Neolithic evidence from the Northwest Quarter was discussed. Two obsidian pieces from Turkey have been found in late and very disturbed contexts, and they definitely came from another area.

Don Boyer (DBo): The Role of Landscape in the Occupational History of Gerasa and its Hinterland

In the paper by DBo two main questions were outlined and discussed: What are the key diachronic elements in the landscape history of the two valleys (the Jerash Valley and the Majarr-Tanur Valley east of Jerash)? And what role did landscape play in the establishment and development of the city and its hinterland?

To answer these questions the area and its substratum must be mapped. Satellite data and interpretations of old aerial photographs from before excavations began are helpful, and slopes and knick points (vertical erosion that appears as waterfalls in the landscape) can be mapped.

In this area the first human activity was in the Acheulian period (in the Paleolithic Age). The main landscape features have their origin in the Pleistocene (ca. 1 mio. years ago). Here the ‘Jarash Conglomerate Deposition’ was formed in the two valleys, and it is this that we find in Jerash, not the cretaceous limestone. As one goes further south, deeper and older rocks are found, and it goes from limestone to sandstone. In Jerash, the different phases are as follows: ‘Jarahs Conglomerate Deposition’ ? deformation and erosion phases ? calcretisation event ? formation of terra rossa soils (on top of calcretite surface) ? major landslip events (on the eastern bank of the city, the landslip events created the area called ‘east bank terrace’) ? wadi incision ? main east bank springs established. In the Late Byzantine Period gravels washed down, and the integrity of the whole city must have been threatened.

The rainfall in the area also has important implications for understanding the settlement pattern, and the impact of microclimatic systems needs to be examined. DBo showed how rainfall declined through the Roman and Byzantine Periods with a few peaks, for instance around AD 600. Before the Bronze Age there was occupation in both the Jerash Valley and the Majarr-Tanur Valley, but there is an absence of Chalcolithic sites in the north. The Majarr-Tanur Valley was abandoned over time, and there were not many sites in the Ottoman Period. Though soil and spring distributions are similar in the two valleys, the bedrock geology is different and the spring strength is different. In relation to all of this the water systems of Jerash are being investigated: canals and aqueducts leading water to the city; springs in and around the city; irrigation in the southern valley; reuse of and loss of access to springs and canals in later periods. The western wadi was chosen due to, among other things: availability of strong water sources (led in from outside), elevated terrain, easy access to rich farming areas in the valley to the north and the south, geology/geomorphology which was optimal for hypogeum tomb construction.

Next DBo touched upon the east side of the city, which is far less explored due to the Circassian settlement here. The Circassian settlement would not have been irrigated from the canal just west of it, because it lies too low – instead there were springs. And it was argued by DBo that some people must have lived here in the Byzantine Period, since six churches were built. Also, an old water colour done by William John Bankes was highlighted. In this it is possible to see the ruins of a larger building, maybe a temple. Perhaps the strong springs on the east bank attracted water based activities (baths, and cults(?)). DBo ended the lecture by urging that archive material be published and made available since valuable knowledge about the east bank can be found in this.

In the discussion it was emphasised how DBo’s investigations and results correlate with the finds relating to water management in the Northwest Quarter. Furthermore clay deposits, 14C date of the canal, the eastern bank of Jerash and the gravel wash were discussed: regarding clay deposits, DBo suggested that substantial resources must exist on the route to Ajlun, and it was mentioned that 35.000 m3 could be found in the hippodrome; regarding 14C dates of the canal, DBo explained that these were taken from the charcoal from the plaster – the rock-cut canals where prone to damage, and they were constantly repaired; regarding the eastern bank of Jerash, it was put forward that the churches here were not necessarily an expression of a substantial Christian population, since you do not need to live in the place where you donate a church; regarding the gravel wash, the piles of gravel found by the Artemision were discussed – where did it come from?, when did the gravel wash stop?, and does the stratigraphy of the Artemision excavations tell us anything about piling the gravel in one area?

Genevieve A. Holdridge, Kristine Thomsen, Søren M. Kristiansen (SMK) & Ian Simpson (ISi): Soils, Sediments and Environmental History: Introducing Geosciences to Archaeology at Jerash

This paper was given by Ian Simpson and Søren M. Kristiansen. ISi began the lecture talking about how geosciences may contribute to archaeology and more specifically to the archaeology of Jerash, where their geoscientist team has been working for 18 months in connection with the Danish-German Jerash Northwest Quarter Project. Geosciences provide new ways of thinking about the site and its hinterland, and it becomes possible to look more into the questions of how the city influenced, changed and adapted its environmental hinterland and how the urban environment developed over time.

Soil and sediment properties reflect the biophysical and cultural environments in which they are formed, and this enables us to reconstruct environmental changes in the natural or/and cultural environments. This way of reading the hinterland was illustrated by the different methods used: with Particle Size Distribution (PSD), the different proportions of sand, silt etc. are identified, and when fed into graphs and statistics this provides us with an environmental record; Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) is a dating method measuring the energy background radiation in the soils, and with a dose rate put together with the stored dose we will get an age of when the material was accumulated; also the shapes of the particles add valuable information regarding the movement of material. Thus, the stratigraphy can be identified and a tight chronology for the hinterland can be built up. It is especially interesting to look at the terracing process and at movement of materials in the wadi and the upper part of the landscape. In the wadi, the team has worked in three different places, and an OSL date of AD 640 plus/minus 120 years has been established.

SMK continued the paper with a presentation of Remote Sensing-methods and results. Comparing new (2015) data from the Royal Jordanian Society and older aerial photographs (1939 and 1953 put together and overlapped) it becomes possible to model the landscape and look for changes. The LiDAR-data from 2015 and the different stages of interpreting it (digital terrain model, hill shade, residual relief model, sky-view factor) was explained, and it became clear that the LiDAR-data has offered new insights into the features and roads on the ground. And by comparing the data with the old photographs unknown structures have been revealed.

Thereafter ISi explained how soils can analysed by thin section micromorphology and ICE and XRF analyses. In the thin sections, cultivation activity can be seen, and in both thin sections and ICE analyses pollution indicators can be observed – lead and copper levels in the soil was pointed out. The limestone mortar from the site’s occupational surfaces and water management systems is also being analysed by the team with thin sections and SEM-EDX analyses, and these reveal temper, structural characteristics and contrasting composition of the mortar.

In the following discussion the lead and copper levels received attention, and it was clarified that an enhanced concentration of lead and copper in a specific area within the city may be associated with coin work. Also the OSL dating of AD 640 plus/minus 120 years was discussed further: does this indicate that the population degraded before the large earthquake of AD 749? It would be important to find a closer date, and the team is also working on that. Also radiocarbon dates will supplement the data and hopefully narrow down the date. Thus, it will be interesting to see if it is possible to get closer to an answer to: What came first – a worse environment or a site abandoned by the population?

Louise Blanke (LB): Suburban Life in Southwest Jarash from the Roman to the Abbasid Period

In 2015 the Late Antique Jarash Proejct was initiated in the Southwest District of Jerash, from the congregational mosque towards the south theatre and towards the church of Saints Peter and Paul in the west. The area slopes up towards the west, and the top of the hill (ca. 100x8 m) has been the main focus for the project. Beforehand this area had not really been investigated, since earlier excavations focused on the churches and the decumanus. The project seeks to reveal more about daily life in a suburban part of Jerash, and in this specific presentation by LB, the results from the two campaigns were presented drawing also on the evidence from the Islamic Jarash Project (see lecture by AW).

The area was recorded through survey, geomagnetic investigations and excavations. The geomagnetic investigations confirmed the street grid that could be seen on aerial photographs, and it is clear that it follows a different alignment than the bath house found under the mosque by the decumanus/cardo. It was an older grid that existed already before the bathhouse was built. Regarding the water supply of the area, a reservoir for water (the sources of which are not identified) was found along with ten cisterns. Most of the cisterns were found in the courtyard of a residential building. For one of the cisterns five phases of use were observed: in its fourth phase it was turned into a garbage dump with, among other things, a gem for a ring, a grinding stone and many juglets and ‘Jerash bowls’ (15.000 sherds were retrieved), and it has been interpreted as discard from a shopkeepers store.

On the top of the hill, at structure with five rooms was found. The southern part of the building evidenced that it collapsed in a single violent earthquake, where after it was abandoned. Twenty-two nearly intact vessels were found in a room, some in hard black basalt close in shape to some found in Jerusalem and Pella (8th–9th century AD). Also knifes, grinding stones and looms were found (in use from 3rd to 9th century AD). The AD 749-earthquake was devastating for some parts of Jerash, but large sections to the south were restored, for instance the mosque and the residential area. In the Abbasid Period the houses were oriented in a different way than before, and there is now a concentration of people along the diagonal street in this area and the decumanus. Each house it seems was responsible for collecting water and was equipped with its own cistern.

After the Southwest District was no longer inhabited, agriculture played a role here (13th–14th centuries). Fields were placed on top of collapsed buildings, and it is clear that they were deliberately deposited for the purpose of farming (which must have been a major communal endeavour). The area was transformed from urban life to farming.

LB ended the talk by telling where the excavations will take place in the next campaign, in order to find out more about the daily and religious life of Abbasid Jerash.

The discussion revolved around three themes; Abbasid and Mamluk evidence in Jerash, the fields and the street system. It was emphasised that there is a difference in habitation periods in the Southwest District and the Northwest Quarter, where there is no Abbasid material, but on the other hand there is Mamluk material. In the Southwest District only few sherds from the Mamluk period have been found related to the field systems, and no structures. The fields were discussed further, and it was pointed out by LB that it is not clear whether they are Circassian or earlier. The Mamluk sherds found in the agricultural layers may date them earlier, but they could also have ‘travelled’ here later. Closer to the mosque there are evidence of Circassian agriculture, but the ceramic evidence here is very different than the evidence from the hill top. The possibility of looking at the soil to see what was grown and to see if this correlates with the written sources was also suggested, and LB mentioned that soil samples had been taken – but not yet analysed. The decumanus and the street system were also discussed. The decumanus continues to the west gate, but it was not covered with stones on the whole stretch – however, it was an actual street and there was a western gate! Regarding the street system in the Southwest District, LB stated that it predates the Roman gridded street system (which is different than in the Northwest Quarter where the street system is quite late, perhaps 4th century AD or Byzantine Period). The project of the Southwest District will in the next campaign look more into how the area was bound into the rest of the city, and excavations on some of the streets will take place.

Alan Walmsley (AW): Urbanism at Islamic Jarash: New Readings from Archaeology and History

The paper given by AW focused first on research on Islamic sites and his own way into research in Jerash, and second on the excavations carried out on the mosque.

Sources from the 10th century AD mention different towns. For a period these were not believed to be real sites, but it has now been established that they are. Great Islamic cities were examined after the World War, for instance Aleppo and Latakia, and from the 1960s interest had extended to looking further afield, for instance to Anjar in Lebanon. Then in the 1970s and 1980s field work expanded and there was an interest in the ‘Syro-Palestinian transition’ from Late Antiquity into Islamic times: what stayed, what changed and what was left behind? Amman, Pella and Jerash were now investigated. In the 1980s AW was part of the explorations in Jerash, and looking back he recounts that archaeology at that time generally skewed the settlement history by personal biases.

In 2002, excavation by the decumans-cardo intersection began. At this point it was not known that a mosque was here, but comparing with the cityscape of Anjar, this would be a reasonable place to look for it. Kraeling had already described the building, but instead of identifying it as a mosque, it was identified as a guard house. Aerial photographs gave away that a courtyard building bent a bit away from the street grid (towards Mecca), and there was a tower in the northeast corner – both features expected in a mosque. Thus, they began excavating for the mihrab. And they found it.

This made it possible to investigate the act of building a mosque and the impact it had on the town – building a mosque was a complex process and would have had implications. Before they started working, they not only knew that there was a mosque in Jerash, but also that it had had a long life. The mosque was constructed ca. AD 725–740 in six stages of construction and inspired by the great mosque at Damaskus. From the mid-8th century to the mid-10th/11th century AD alterations and additions were made. The chronology is not so clear as in the earlier stage, but it is clear that the mihrab got blocked, and a new mihrab was built next to it; a northeast tower was built (early version of a minaret); a new entrance area to the court yard was created and more. The mosque collapsed in an earthquake, but was restored to some extent before it was abandoned. Afterwards it was an open area, and Ayyubid and Mamluk ceramics were found here.

Below the mosque they found a bath house that had been demolished and partly reused. On the west side of the mosque were residential buildings and to the east (opposite the cardo – and in the ‘round crossing zone’) were markets.

The following discussion first led to talk about other mosques in Jerash. There is one in the northern part of the city (perhaps Mamluk), and AW also speculated whether there is one more near the south decumanus where we find so much Islamic activity. Next there was shed more light on the mihrab, in which no minbar was found. But, the only piece of floor (nine colours) that existed in the mosque (from the first phase) was found in the area where the minbar should have been. The minbar had probably been moved – maybe it was made of wood and taken out when it was not used. Last, chronology and earthquakes were discussed: Could the mosque not have been built after the devastating earthquake of AD 749? The walls do not look shaken, and that earthquake could then have demolished the bathhouse on top of which the mosque was situated. It is a possibility, but AW argued that after the earthquake it was dangerous times and not likely that anybody would built the mosque, and he also comments that the mosque may just have been solidly built – there are places where one building collapses and the one next to does not.

Georg Kalaitzoglou (GK): The Northwest Quarter of Jerash: Outlines of a Settlement History

In his paper on the Northwest Quarter, GK outlined the settlement history of this area of the city, highlighted important finds and considered what happened to the area after habitation. Before excavation were begun here, only the synagogue church had been excavated (in the 1920s), and a large cistern was known. Now, around 1.500 m3 have been excavated. The strategy was not only to excavate one part, but to concentrate on different important spots that would help to give an overview of the area; for instance, spots where walls meet, where buildings could be expected, and where terrace walls began.

The earliest traces in the Northwest Quarter are quarry marks. The cistern, known before excavation, turned out to be from the 2nd century AD (dated by plaster), and this was one of the places where the earlier quarry marks were found (from an earlier Roman Period). There are quarry marks in many places in the Northwest Quarter, and it is clear that they tried to win blocks wherever it was possible (where the limestone was hard enough – on the north-side it was too soft). As to when the city wall should be dated, the trenches made here could not provide any answer. There was almost no pottery in situ. Inside the city wall drain and water pipe was found, but there was no hole in the wall, so the drain and water pipe did not go through the wall.

By the large cistern, a sediment basin was found just north of it. This fell out of use in the 5th century AD. A new quarter was in the beginning of the Byzantine Period established north of the street by the cistern. By another cistern found on the top of the hill, no sediment basin was found, and where the water came from is still an open question. This cistern was organised in two chambers separated by a dividing wall and covered with arches. There were no finds connected to the construction of the cistern, but mortar dating and radiocarbon dating may tell us more. In the fill several Late Roman cooking pots were found, and these help to date the destruction of the cistern.

Another interesting find was two caves below a Mosaic Hall (see lecture by AL and RR). In the first phase, the caves had been used as oil presses and oil mills, and in the northern cave were found three basins on the west side, where the oil would have been collected. In the Byzantine Period it was filled in and overbuilt by the Mosaic Hall. This originally had one mosaic with inscription, and around 15 years later the building was extended to the west and a new floor with a new mosaic inscription was laid. A lot of Umayyad-Period material has been found here. Thus, the building was not destroyed despite of a change in rule, and the building had a long life. There is a lot of evidence from the Byzantine Period both in regard to habitation and water supply. Among other things, a large rectangular building was found on top of the hill with a courtyard and small rooms next to. With geomagnetic survey results more can be added to the structures found in excavation.

Next GK tackled the change of rule and how this is seen in the material record. Structures were reused, and a lot of Umayyad-Period material was found in the rooms of both the rectangular building and of the Mosaic Hall. The large cistern was given up and turned into a terrace. But new buildings were also built, for instance on the east terrace where private houses, presumably destroyed by the earthquake of AD 749, were found. The walls were found collapsed, and pieces of mosaic floors, the mouth of a rock-cut cistern and a water pipe leading to the roof were found in a house.

In the Ayyubid and Mamluk Periods a settlement, or hamlet as it is termed because of its small size, existed on top of the hill. In a house three different floor levels were found, and these buildings are the latest that can be identified on the hill top. The latest pottery in the Northwest Quarter is likewise Mamluk (perhaps Late Mamluk), but this Middle Islamic pottery is hard to date, and it is hoped that a typology can be created. Plough marks were identified on top of the buildings, which indicate that the area was cultivated. But where is the soil? And when were the plough marks made? Presumably the Circassians used the area for agriculture.

The discussion got around the caves used for oil making, the plough mark, sewage and the large rectangular building: it was questioned whether the caves could not have been used for wine instead of oil, but all the typical installations for olive oil production have been found here (for instance the typical crusher for crushing the olives); the iron plough came with the Circassians, and the wooden ploughs used before this could not make the plough marks – thus, the Circassians must have been responsible for the plough marks; regarding sewage, it became clear that only one drain (near the city wall – and thus leading the sewage in this direction) had been found in the Northwest Quarter. The channels below the streets were for providing water, not for getting rid of water; ideas for the use of the large rectangular structure were expressed before the discussion ended, and a structure related to the Electi Justiniani, barracks and reservoir were suggested.

Massimo Brizzi (MB): The Artemis Temple in Jarash: Overreaching or Resistance?

In the paper given by MB the Artemis Temple, the building sequence of the Antonine temple and its appearance were highlighted. Despite many years of excavations and examinations of the sanctuary, there are still many unsolved questions in relation to both the appearance of the temple and the construction of the temple.

It seems as though the temple was planned in one way but executed in another way. Construction began with the temple, and after this the colonnades around the area were built. The row of columns of the temple was built first, and after this the cella was built, and by the back part of the cella was a massive platform. The blocks used for the columns have graffiti or marks, which would have let the builders know where the blocks should join each other – these marks, however, are not found in the blocks of the cella walls. One capital has an inscription, ???????? – a specialised artisan/craftsman, who was allowed to sign his work. This signature has also been found in another place in Jerash (the Macellum). The thalamos in the cella was built independently from the rest of the structure, and in order to realise the construction of the thalamos, the cella wall had been cut to half the thickness of the original wall. The wall had already been built, but they changed plans when building the thalamos. In order to get to the roof, which MB believes to be a terrace and not a gabled roof, stairs in the north side of the thalamos would have led people by the cult statue to reach another set of stairs going all the way to the roof. On the floor of the temple were found pieces of marble, and following the patterns of the clamp holes in the cella walls it is easy to see that the marble revetment had pilasters with capitals and bases. The revetment consisted of different kinds of marble, for instance giallo antico which is rarely found in this region.

At the end of the paper, some of the other structures of the sanctuary were explored: the altar, Antonine in date, with its huge foundation and surrounded by ten bases, and the exedras of the so-called Trapezoidal Square opposite the road, which MB presumes would have held statues of emperors. By the 5th and/or 6th century AD huge layers of earth were deposited here, and this unfortunately makes it very expensive to investigate the early layers of the sanctuary.

Stone quarry, altar and earlier phases were taken up in the discussion: the quarry for the huge stones of the Artemision is around 15 km away from Jerash, and there are still drums to be seen in the quarry; the altar was probably a tower altar like those in Baalbek – spolia from the altar were used in churches (among others, in the Church of St. Theodore); below the Trapezoidal Square the excavations did not go so deep as to be able to answer the question of what lay here beforehand, but a lot of plaster from a destroyed building was found here.

Thomas Lepaon (TL): The ‘Great Eastern Baths’ of Jerash/Gerasa: Balance of Knowledge and ongoing Research

In the paper by TL, the new excavation and research project revolving around the ‘Great Eastern Baths’ of Jerash was laid out, and the results until now were shown. Besides aiming at doing archaeological, architectural, sculptural and environmental (geo-morphological) investigations, Jordanian students are trained in excavation and post-excavation work. The baths is an important building on the eastern side of the wadi, and it can be found on the plans of the earlier travellers: for instance, on the plans of Buckingham, Burckhardt and Warren, and it is also in the 1938-publication by Kraeling. However, the most precise is the oldest source, namely William John Bankes’s drawings.

In the 1980s and 1990s some investigations in the baths revealed parts of its ground plan, among other parts, the so-called North Hall which is the focus of the new project initiated in 2016. In the North Hall, marble statues would have stood on inscribed bases (some square, some round) probably placed in front of the columns. The bath complex occupies an insula 240 m long and 116 m wide, and six phases of the baths have been discovered: the baths were constructed in AD 170–200 (phase 1), but the North Hall and its annexes were first built in AD 250–300 (phase 2). In the Byzantine Period into Umayyad times (phase 3), the building was reoccupied and decorative elements were reused. The building was then demolished (by the earthquake of AD 749(?)) (phase 4), the ruins were reoccupied (phase 5) and at least abandoned (phase 6).

In 2016 two trenches were excavated, and besides learning more about the phases of construction, remains of a pool, marble floor, and marble sculpture were found. As for the sculpture, a portrait head resembling Julia Domna, but probably being the portrait of another female from the Imperial court or of a local noble woman, was found. Also a statue of Aphrodite with Eros riding a dolphin and an inscription dating it to AD 154 was found.

In the following discussion the end of the bath complex as a bath was tackled first. Two baths in Jerash are known to have been in use in the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD, but when they began working and when this ended is not known. Next, industrial use of the building was discussed, and it became clear that though their might have been evidence (perhaps gone now) for industrial use in the area, there was no evidence for this in the bath building. The statues also received attention, and it was emphasised that the statues most certainly came from somewhere else – and whether the arrangement of the statues in the North Hall were from the Roman Period (as the statues themselves) or later must be clarified in the future campaigns. The reddish soil that could be seen around Aphrodite found interest with the geoscientists, who asked that soil samples be taken. Last but not least the water supply for the baths was discussed, and it was argued that the baths were built due to 1) the access to water (Ain Karawan) and 2) because of the space – there was enough space to build what they wanted. In this connection, the ?-shaped palaestra was discussed further.

Daniela Baldoni (DBa): A Byzantine Thermopolium on the Main Colonnaded Street in Gerasa

A room built next to the workshops in front of the Artemision was investigated in 1991–1992 by the Italian mission, and this room was the focus of DBa’s lecture. The room is also located by a side street (not the north decumanus, but a smaller street) of the cardo.

The initial use of the room (in the first decades of the 2nd century AD) may have been connected with a cult. It is difficult to establish the original function, but terracottas of Aphrodite and Tyche may confirm this interpretation. The room was clearly part of a larger complex, the layout of which has been impossible to determine. The room itself had an upper storey, it had a semi-circular niche, a door to the south-east and another flight of stairs originally as wide as the width of the room. The ceramics belonging to this phase consisted of locally-produced table ware (clay fine or semi-coarse, thin slip applied when the objects were upside down, slip vary from red to brown, imitate ESA ware), especially plates and bowls, but also jugs, bottles and cooking pots. Other finds included: lamp from 2nd century AD, coin with Marcus Aurelius, coin minted at Bostra in the second half of the 1st century AD and 19 coins in a coin hoard attributed to mid-4th century to mid-6th century AD. Use of the room continued until the mid-4th century, but whether it was with the same function is not sure.

Hereafter the building was abandoned for a long time, and at some point in the Byzantine Period the area was restructured, and the room was turned into a thermopolium. The finds establish that it was a place, where food was served as well as it was prepared here. The room was now equipped with a counter or table (the feature supporting this was found), a U-shaped bench for customers, and pots sunken into the floor in different places (used as waste containers). An abundance of table ware and storage jars were found, including locally produced ‘Jerash bowls’. Also glass vessels, knifes and a mill stone reused as a mortar were found. In the southern part of the room a thick ash layer containing charcoal and animal bones were discovered, and in the layer were three ‘Jerash lamps’ and two cooking pots. In some of the vessels was residue of food. Also 65 bronze coins were found in different smaller hoards. These may have been deposited by one of the occupants of the structure – the savings of the occupant (or perhaps income)! The room may have been destroyed by the earthquake of AD 660.

Concluding the paper, DBa drew attention to other known tabernae/thermopolia in Sagalassos, Sardis and Scythopolis. Reliefs and mosaics tell us much about Roman tabernae/thermopolia, but not much is known about the Byzantine taverns (and not at all much in the eastern part of the Mediterranean). Hopefully the finds from Jerash can help identify similar buildings in the Byzantine east.

The discussion revolved around the ceramic finds, and the residue of food in the vessels was discussed in more detail. It was not in the cooking pots, but in a bowl, and an analysis of it has not yet been made. However, it is almost certain that it is food remains, since it is not like pigments. Also a ‘simple beaker’ from the presentation was emphasised. This type was found in large quantities from the Byzantine Period, whereas there are none from the Umayyad Period (the room had presumably been demolished at this point in time). In the Northwest Quarter this type of ‘simple beaker’ is not found in the Byzantine layers, but instead in the Umayyad layers.

Second day - 3 March 2017

Ali Al Khayyat (AAK): The Challenges Facing Jerash Archaeological Site Development

AAK gave an open and honest paper about the problems – legal, financial and technical – in relation to archaeological sites in Jerash and Jordan. It is difficult to find a balance between tourists, awareness of the local population and research/excavation, and it is not only the responsibility of the Department of Antiquities in Jordan (DoA), but also of the researchers/excavators and civilians to protect the archaeological sites.

DoA was established in 1923, and it is the governmental authority responsible for implementing archaeological policy (law no 21 from 1988). There are around 100.000 archaeological sites in Jordan, and in the last ten years 27.000 sites were registered. This entails a large budget and demands a large staff, but the financial means are not enough to take care of all the things that they would like to, nor for having enough employees in the DoA.

The western side of ancient Jerash is owned by the DoA, but on the eastern side of the wadi, only small parts are owned by them. Local people have their homes here now. It would cost around 36 million JD to acquire the rest of the archaeological parts in the hands of civilians – since the DoA every year has 400.000 JD at their disposal (and of these 30.000 JD goes to Jerash), this is not a possibility. Especially the city wall of Jerash and the store and museum facilities were discussed in more details: the city wall with its towers encloses the archaeological site on the western side of the wadi, and today it is marked with an iron fence. However, parts of the wall and towers are outside the fence and therefore not protected. The eastern stretch of the wall has been destroyed by the houses built here. For storing the archaeological objects, the facilities in Jerash are not optimal – objects are stored in a primitive manner that does not serve to maintain them, and the museum does not receive the finances that are needed for preserving the artefacts, for developing scientific methods and for telling the history of Jerash to the tourists.

It is time to reconsider the purpose of excavating, when restoration and preservation are not an integrated part of the work done at the archaeological sites. Of the many international projects, only around 10% of them are occupied with maintenance and restoration. AAK states that it should be part of all students’ education that they learn about protection of the site. A plan regarding maintenance, restoration and rehabilitation should be made by the same team that is excavating. A new law has just been finalised, and with this it is hoped that some problems can be solved. It concerns the management of the sites, publicly or privately managed. And it is hoped that the two different laws regarding tourists and archaeology can be placed under one umbrella.

Also in connection with preservation, it is important that the locals cooperate. Many houses and also the suq are built from archaeological stones, and the locals live right next to the ancient remains. A number of educational awareness programmes for the locals should be conducted, so that they know the value of the archaeological remains in the areas where they live.

The many challenges that the DoA are facing gave all a lot to think about, and the new law, cooperation of locals and the iron fence was put forward in the discussion. The new law and requirements of restoration will be challenging for those projects working on private land. It could be a possibility to make an agreement with the land owners to look after the archaeological sites without touching them. Also, it would be essential to work with the hundreds of collectors in Jordan – give them permission to have small exhibitions. In relation to Jerash, the locals and the iron fence, it was suggested that the fence could be discarded – this would make it easier for the Jerash people to engage with the site and commit. But before this can happen it is important that the site is protected – for instance through awareness. The Ottoman House was also brought up, and AAK told about some plans for making it into an open museum (in the garden), a ‘starting point’/’vantage point’ for visitors.

Jacques Seigne (JS): Why did Hadrian Spend the Winter of 129/130 in Gerasa?

Hadrian visited Gerasa in the winter of AD 129/130, and in this connection the city was reorganised. In the paper, the reorganisation is described, and JS began with the city as it looked before Hadrian: Temple of Zeus, cardo, tell near Zeus, civic complex to the north, south theatre and necropoleis.

First, focus was on the Zeus Sanctuary, and the possibility of this being an oracular sanctuary. The Zeus Temple was rebuilt on a large scale in AD 162, and the temple that was here when Hadrian visited was much smaller. Through excavation it has been possible to say much about the early temple. It was built around bedrock cropping out, and there was a cave above which the first monument was built. A tower-like structure, a kind of hamana, with relief decoration, columns and coloured paintings inside, stood here. This was dismantled when the new temple was built. A small room (less than one m2) and a narrow corridor was found under the platform of the tower structure. Evidence for arguing that the Zeus Sanctuary was an oracular sanctuary, was presented: six scrolls and all the small holes found in the joints between the blocks of the walls, where these scrolls could have been placed; a base for Zeus the Messenger; a base with an inscription mentioning Platonikos Filosofos (who offered an oracle to Hadrian, saying he would become emperor) – was this Platonikos from Gerasa?; also the small room that belonged to the original Zeus Temple could perhaps be connected to the oracular activities. This room seems to have been of importance, and it was kept in the rebuilding of the temple. JS speculates whether this was the place for the oracle. The room was difficult to reach with 1.80 m high door steps and a narrow corridor.

Next, focus was on the Arch of Hadrian built south of the city. It was built in relation to Hadrian’s visit to Gerasa, and the inscription commemorating his triumph was found during the American expedition in 1943. Originally this would have been placed above the middle arch (not on an attica as believed earlier). Some letters had been erased and a new inscription was written on top of the erased part. This phenomenon is seen in other Hadrianic-Period inscriptions from Jerash. The erased part comes after the word Gerasanon, and perhaps the title of the city could have stood here – a title lost after the visit of Hadrian.

Tying it all together, JS argues that the Gerasenes during Hadrian’s visit had planned to extent the city to the south, but immediately after the visit this plan was abandoned. Before the visit, the centre of the city was by the Zeus Temple, and the Arch of Hadrian would extend the city to the south. But as the Artemis Temple, which JS argues should be found on the tell near the Zeus Temple, had to be enlarged there was not enough space. Therefore, it was moved north, and the city developed in this direction instead.

Though no remains of the older Artemis Temple have been found by the Roman Artemis Temple until now, JS’s suggestion was not widely accepted. In the discussion the arguments against JS’s suggestion were mainly based on the fact that sanctuaries do not ‘move’ like that.

Pierre-Louis Gatier (PLG): Romans in Gerasa: A Greek Inscription from the Hippodrome Excavations

In his paper, PLG focused on an inscription found in the hippodrome of Gerasa. The inscription is Greek and it provides valuable information on Romans in the city. The governor of the province sat in Bostra, and two kinds of officials were in Gerasa: soldiers and civil servants – some as part of the procurator office, others as part of financial offices. It is the civil servants that we learn about from this inscription.

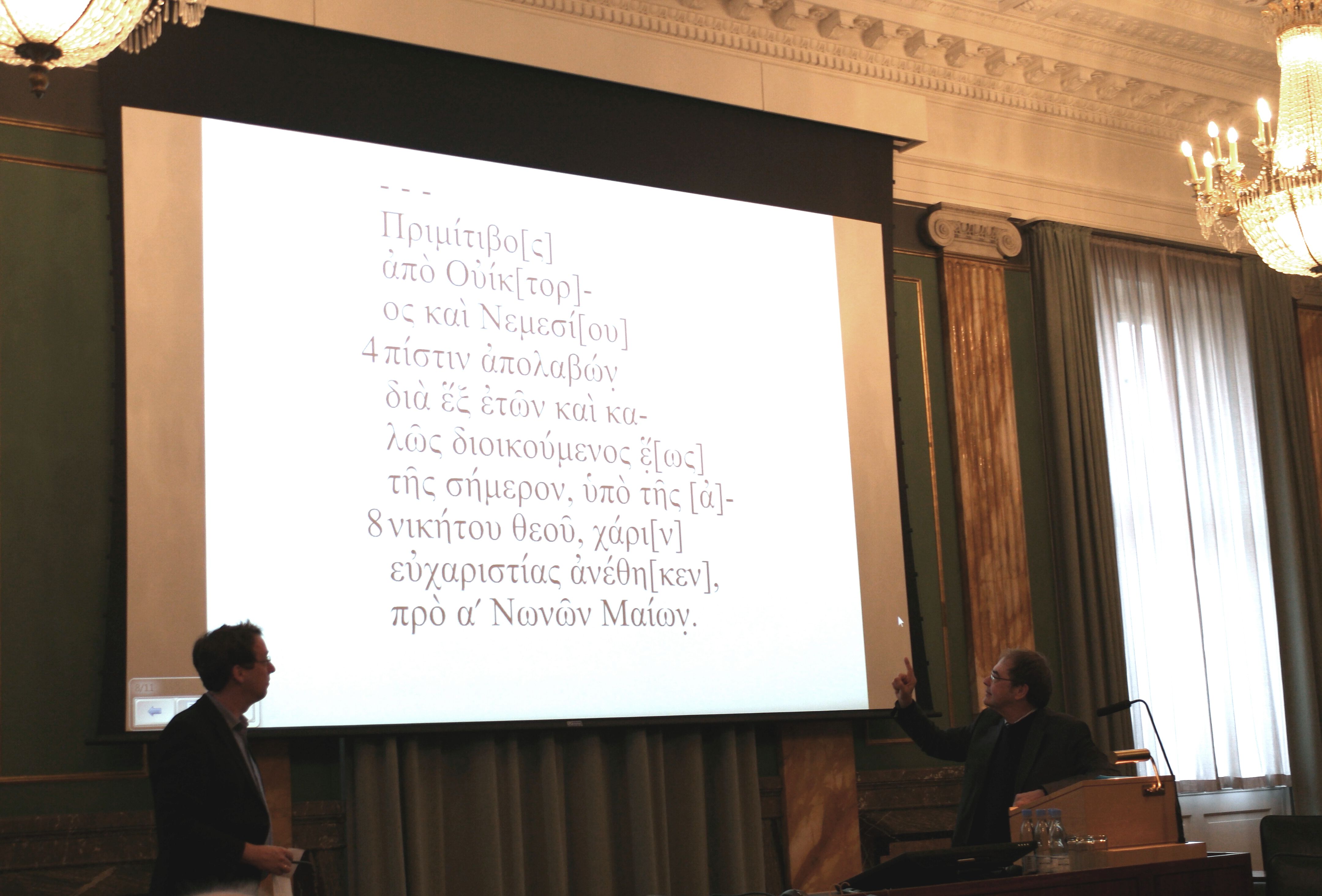

The late Antoni Ostrasz conducted excavations in the hippodrome between 1984 and 1996, and in the season of 1992/1993, the inscribed stone was found blocking the entrance to room E4-E5 in the north-eastern side of the cavea of the hippodrome. Now it is in the depot of the Department of Antiquities. The inscribed stone, an altar, was made of limestone, and it had been recut to be put in a building. Thus, moulding and base were destroyed, but the main part was nearly complete with inscribed letters 2–4 cm long. The inscription that would have been on the moulding (probably dedicating it to a deity) is missing. The letters vary in shape, for instance the omicron could be both round and square.

PLG translated the inscription, and gave a detailed analyses of the individuals mentioned in the inscriptions. The first one up was Primitivus, who dedicated the altar. He has a typical slave name, and from the inscription it seems certain that he was a civil servant in an administrative position in the financial office of the equestrian procurator – and this position he got six years earlier. Next Victor and Nemesis were analysed. Though they are only presented in the inscription with their cognomen, they may well be Roman citizens, and they could be either colleagues of Primitivus or of a higher rank. PGL suggests that Victor was governor in the 3rd century AD. The deity for whom the altar was set up was discussed next, and based on the fact that she is called ‘invincible’ in the text, PLG suggests Nemesis (Nemesis is the only goddess to be called invincible in the Roman Empire). She is also the goddess of faith, and the word ptistin (akk. of ptistis – faith) also appears in the inscription.

The inscription is the only one using the Roman calendar (typical of Roman administration), which is very rare in the Near East – four other examples in Greek, all form the 3rd century AD, are known to PLG. He dated it to the first half of the 3rd century AD.

In the discussion the calendar was further discussed, and it was clarified that it is very normal to use a Roman name of a month in inscriptions (for instance this is seen in the Electi Justiniani inscriptions in the Northwest Quarter – see lecture by AL and RR). They used the Greek system for the date, and the Roman system for the month. Consular years, on the other hand, are only found in few inscriptions. Nemesis in Gerasa was also taken up, and only one other inscription from Gerasa mentions Nemesis. Next the original location of the altar was discussed. Presumably it had nothing to do with the hippodrome, but instead it came from the area around the Zeus Temple.

Maysoon Al Nahar (MAN): Tell Abu Suwwan, Jerash, Jordan: Neolithic Skulls and Rituals

Tell Abu Suwwan, located south of the hippodrome and very close to the Roman city, is a so-called mega-site from the Neolithic period. In the paper by MAN the site and the interesting results from the excavations were presented.

The new excavations began here in 2005, but before that different surveys and excavations had already taken place. However, these concluded that no architectural structures were on the site – but that was disproved by the new excavations. In two areas, A and B, were found structures. In area A, a small structure, around 2x2 m, was found together with remains of a plaster floor. However, most had been bulldozed. In area B a much larger structure was unearthed, around 13x12.5 m, with walls 1-1.20 m thick and with a 3 m wide platform in front. They found different layers of plaster floor, painted red by ochre, and it has become clear that the structure was not built at one time – for instance, the platform was originally a room, that was later filled in to function as platform. Also tools, mudbricks and pottery were unearthed.

Just east of the structure in area B was an area with many mudbricks, and the discovery of burials here has clarified that this was a ritual area. There are both complete burials, secondary burials (reburial after skull had been removed) and burial of skulls. It is the same situation as known from Jericho, where skulls were taken up after a period of being buried, and here they were plastered and shells were put in the eyes. At Abu Suwwan they also found shells by the skulls, but the plaster in the eyes had vanished (because of water?). Also obsidian was used in the eyes of skulls in Abu Suwwan. MAH speculated whether some stones found within a circle (and just outside the circle) were meant to represent human organs – this interpretation is based on the fact that one of the stones resembles very much a heart.

This village here at Abu Suwwan dates to the Middle Pre-Pottery-Neolithic B, and it was settled continuously for more than 4000 years – ca. 8500–4000 BC.

Especially exchange of artefacts and ideas in the Neolithic period were subjects taken up in the discussion. Abu Suwwan and Ain Ghazal must have exchanged things, since many of the same things are found in the two sites. Stone tools were for instance exported from Abu Suwwan. Many thousands of scrapers were found here, and a few in the same shape have been found in Ain Ghazal – these came from Abu Suwwan. The obsidian and its presumed origin from Anatolia also initiated a discussion of the similarity in architecture between some Anatolian sites and Abu Suwwan. In this connection, it is very interesting that Abu Suwwan was earlier than the Anatolian sites with similar architecture. The size of the settlement/village on Abu Suwwan was described as matching that of Jericho. Surveys in the area around the site have only traced sites that seem to be small. Also the protection of the site was discussed. Since the land is privately owned, there is not much they can do in regard to preservation. MAN would like to have a shelter protecting the structures (that are very strong), and it could be a fine place to open a small museum.

Heike Möller (HM): High Pottery Quantity: Some Remarks on Ceramics in Context from the Danish-German Jerash Northwest Quarter Project

In this paper by HM an overview of the work done so far in relation to the pottery found in the Northwest Quarter during the last five years was presented. First, fabric and typology was discussed. Regarding the latter, HM argued that it has become very difficult to compare ceramics and typologies, due to different categorisations within the ceramic material. Her own way of categorising the pottery is based on function (transport, storage, kitchen etc.). A lot of kilns (especially from Byzantine and Umayyad times) have been found, and there was a lot of pottery production in Jerash. This had to do with easy access to natural clay deposits, which HM suggests were found in the wadi (the samples taken, however do not confirm this). The fabric – and the ‘chemical fingerprint’ of the fabric – helps establish whether the ceramic is local, regional or imported. Local fabrics could have both a grey and an orange colour – a re-firing experiment showed that sherds get a more orange colour as they are fired again, and thus, the colour is a matter of firing, and not only of fabric.

Next, HM focused on one context from the Northwest Quarter – trench J next to the synagogue church (see lecture by GK). In this trench two shafts leading down to caves were found filled with high quantities of pottery (practically no soil was here). The pottery is in good quality, and it included some complete cooking vessels and jugs. There was a large variation of all functional groups. In one shaft, pottery dating mainly to the 3rd and 4th centuries AD was found. However, also younger sherds were found, but only few (that is, less than 1%). Does this mean that the shaft was reused later, or does it indicate that the shaft was not filled in during the Late Roman Period, as first thought, but at a later point in time? In the other shaft less than 1% of the pottery was younger than the Umayyad Period. Another interesting observation in relation to the two shafts is that the pottery in one was grey ware, while the pottery in the other was mainly orange in colour. Does that tell us something in relation to chronology?

Lastly, regional networks were drawn forward, and the question of how we can see if the ceramics are local or regional was put forward. When is the clay local or not? Do we have to go far away to find another pottery centre? As for imported goods in Jerash, amphoras from the Baetica area, African Redslip Ware and eastern Mediterranean imports were highlighted. Analyses made on the imported wares reveal a marked difference in the composition of the fabric.

In the discussion it was noted that there is a great diversity in material from this single area, and that it is interesting that there is such continuity in shape from the Roman Period to the Umayyad Period. Some shapes are so essential that they keep their shape. Specific shapes and pots were drawn forward and discussed. For instance a bowl that changed size during time: in the Roman and Byzantine Periods only small bowls existed, whereas they are large in the Umayyad Period. Also repairs on ceramics were highlighted. In Jerash, as well as in Pella, ceramics that (to us) do not seem to have been so valued were repaired. The ancient people would presumably have seen it in a very different way, and have valued their things in a different way. Repairs were not necessarily done because they could not afford new ceramics. A final note was made about Gadara, where they imported cooking pots from Syria.

Ingrid (ISc) and Wolfgang Schulze (WS): Working with Coins in Jerash: Problems, Solutions and Preliminary Results

795 copper coins were unearthed in the Northwest Quarter between 2012 and 2016. These have been studied by ISc and WS, and the preliminary results were presented in this paper.

Most of the coins had a thick patina, were very weathered and also very small (less than 1 gram), which made them difficult to clean. Many needed chemical cleaning, and many were too small to study in a binocular microscope afterwards.

The largest group of coins found are from the Roman and Late Roman Period (however, 103 coins could not be dated). The minimi, very small copper coins, where discussed in greater detail. They were struck in large quantities in the 4th and 5th centuries AD and were poorly manufactured. They fulfilled the need for small change, and unofficial minimi circulated alongside official issues as an integrated part of the monetary system. In the 5th century a shortage triggered that a mass of imitations came on the market, and also older coins were used. This circulation of old coins for a long period presents a problem to the scientists, and ISc and WS emphasised that we should be cautious when dating layers and objects after the coins found in the context. Next Umayyad coinage was analysed. Since a settlement was located in the Northwest Quarter in the Umayyad Period it was surprising that only 64 of the discovered coins dated to the Umayyad Period, including both pre-reform coins (638–697 AD) and post-reform coins (697–749 AD). The pre-reform coins imitate Byzantine coins. In the Northwest Quarter no Abbasid or Mamluk coins were found, but two coins from the Ayyubid Period were unearthed.

The last part of the paper focused on different contexts and new insights offered by studying the coins in them: in a large cistern a large number of Roman coins, no Umayyad pre-reform coins and two Umayyad post-reform coins were found. The coins have helped date the Islamic superstructure here tentatively to the first half of the 8th century AD; in an earthquake-struck Umayyad house on the so-called East Terrace (see paper by AL and RR) were found a hoard of Umayyad pre-reform coins with imprints of textile. Could the hoard have been a collection of old coins? Also interesting is the fact that it was a purely Umayyad house, but Roman coins were found here. At other sites Umayyad coins are regularly found together with large amounts of Roman coins, and with this context it is shown that it had to do with circulation of old coins.

The following discussion mainly revolved around the different contexts and the reform of Abd al-Malik: an Ayyubid much worn coin found in a context with no middle Islamic structures, but with ceramics and a fire place from the Mamluk Period found interest. Also the hoard found in an Umayyad house attracted attention, and it was further explained that it was found near a wall and near a box with a lot of metal pieces – was this metal kept for reuse? Regarding Abd al-Malik’s reform, the replacement of figure-decorated coins with text-decorated coins, a reorganisation for political reasons, over-struck coins, circulation of old coins and bilingualism on the coins were themes that were debated.

Gry Barfod (GB): Forensic Investigations of the Jerash Glass

A small portion of the glass found during the excavations in the Northwest Quarter has been studied, and GB, a vulcanologist, told about the methods of studying glass and the results in her paper. Twenty-five glass artefacts (mainly green and blue) have been chosen for further study, and the results of the studies were meant to give us information on questions such as: Where did the glass come from? Which routes did the glass take into Jerash – from the coast of Palestine and/or Egypt? Which types reached Jerash? And can we find out whether it was recycled or reworked when it arrived in Jerash?

There are two main types of glass: soda-lime glass, which is the earliest type (Roman and Byzantine) and soda-ash glass, which is the later type (Islamic). Soda-lime glass is made out of sand, and lime and natron from Egypt is added. Later plant ash was added, and this resulted in soda-ash glass. For the soda-lime glass there are production sites on the Levantine coast and in Egypt.

To investigate the composition of the glass found in Jerash, samples of fresh glass were needed. These were put into epoxy, polished until they were smooth and then analysed using different machines: electron microprobe (which can give up to 20 elements in the composition of the glass), single collector ICP-MS (60 elements can be traced – and there is only minimal damage and minimal contamination) and multi collector ICP-MS (stronthium isotopic composition is revealed – but the sample has to be dissolved).

These investigations revealed that the glass in Jerash is almost all of the same type, called Levantine I type. Thus the glass was made on the Levantine coast and exported to Jerash. Three production sites have been identified on the coast: Jalame, Apollonia and Bet Eli’ezer. At these three sites the sand varies a bit, and it has therefore been possible to determine that the glass from Jerash was made in Apollonia.

GB also had some interesting results to show regarding recycling/remelting of the Jerash glass. When glass is remelted it gets contaminated by the fuel used – in Jerash, potassium and phosphorus increased, while there was a relatively low calcium and magnesium contamination. This suggests that wood was not used as fuel. Instead GB suggests olive pits, but the olive pits she could do investigations on were all found in relation with limestone, which means that they were contaminated.

The fuel used in the remelting process was taken up in the discussion, and it was mentiond that dung was used as a fuel in Egypt. It was also mentioned that in Jordan, some generations ago, and again now, olive pits are used as fuel.

Final discussion

The organisers opened the final discussion by asking the participants: Where is the research on Jerash at the moment – what should we tackle in the future? And what can be done together?

Exchange of information – among researchers as well as between researchers and the local population – was an issue especially highlighted. The knowledge of the last 110 years should be shared/published, and there is a need to engage more with the local people in Jerash and involve them in their heritage. This is especially important for connecting the two city parts of Jerash – the western and the eastern. The wadi has been like an iron curtain compartmentalising not only the city but also the archaeological work.

Also the great potential of Jerash for investigating an ancient city with numerous periods was emphasised. We should take the change to work diachronically, and to engage with every period of Jerash’s history and with subjects that have earlier been neglected (an example drawn forward was the Mamluk ceramics).

Publication: the conference will be published in a newly founded series Jerash Papers, published by Brepols. Deadline for contributions are 1st of July 2017. All contribution will be peer-reviewed (double-blinded).