Digitizing the Roman Imperial road network

Associate Professor Tom Brughmans discusses the need to digitally aggregate evidence of roads throughout the Roman Empire, and shows how computational network techniques can be used as a Google Maps for the ancient world.

By Associate Professor Tom Brughmans

The Romans built an expansive road network. Thousands of kilometres of very well-designed roads connected regions as far apart as present-day Britain, Morocco, Egypt and Turkey. This network shaped and structured European transport systems in ways that are clearly visible today. In the centuries that followed the Roman Empire, people and goods still very much followed Roman routes, and subsequent kingdoms and empires gradually elaborated and modified the Roman core of the transport system. But even today, many of the key transport routes throughout Europe still follow the ancient Roman transport system.

Many research topics in Roman Studies are dependent on a good knowledge of the Roman road system. How did the Roman military march from one frontier to another, and how were they supplied with the necessary subsistence goods? What routes did inland distribution of grain and oil follow to supply for the needs of urban populations? A good understanding of the Roman road system is even crucial for studies of movements of people and goods in later periods, because this system was so foundational for European infrastructure.

So Roman roads are important. Sadly, this importance is not reflected in the available resources needed for exploring these research topics. To be clear, Roman roads have received vast amounts of research attention, their tracks are very well documented for most parts of the Empire, as are associated objects like Roman milestones and waystations. The issue lies in the aggregation of this evidence and research. Detailed information derived from excavations of parts of Roman roads is often not systematically used to update regional road maps, if such regional aggregations even exist. This has led to a very patchy overall picture: for some regions which have seen a lot of research attention we have a pretty good and detailed picture of the Roman road system, such as Italy, France or Britain; but for other regions there has been very little aggregation of Roman road evidence. Few of these regional aggregations have been digitised and even fewer are openly accessible online.

A highly detailed digital version of the entire Empire that aggregates all known evidence of Roman roads simply does not exist. I find this incredible, given the importance of such a resource for Roman Studies and the sheer amount of attention Roman roads have received.

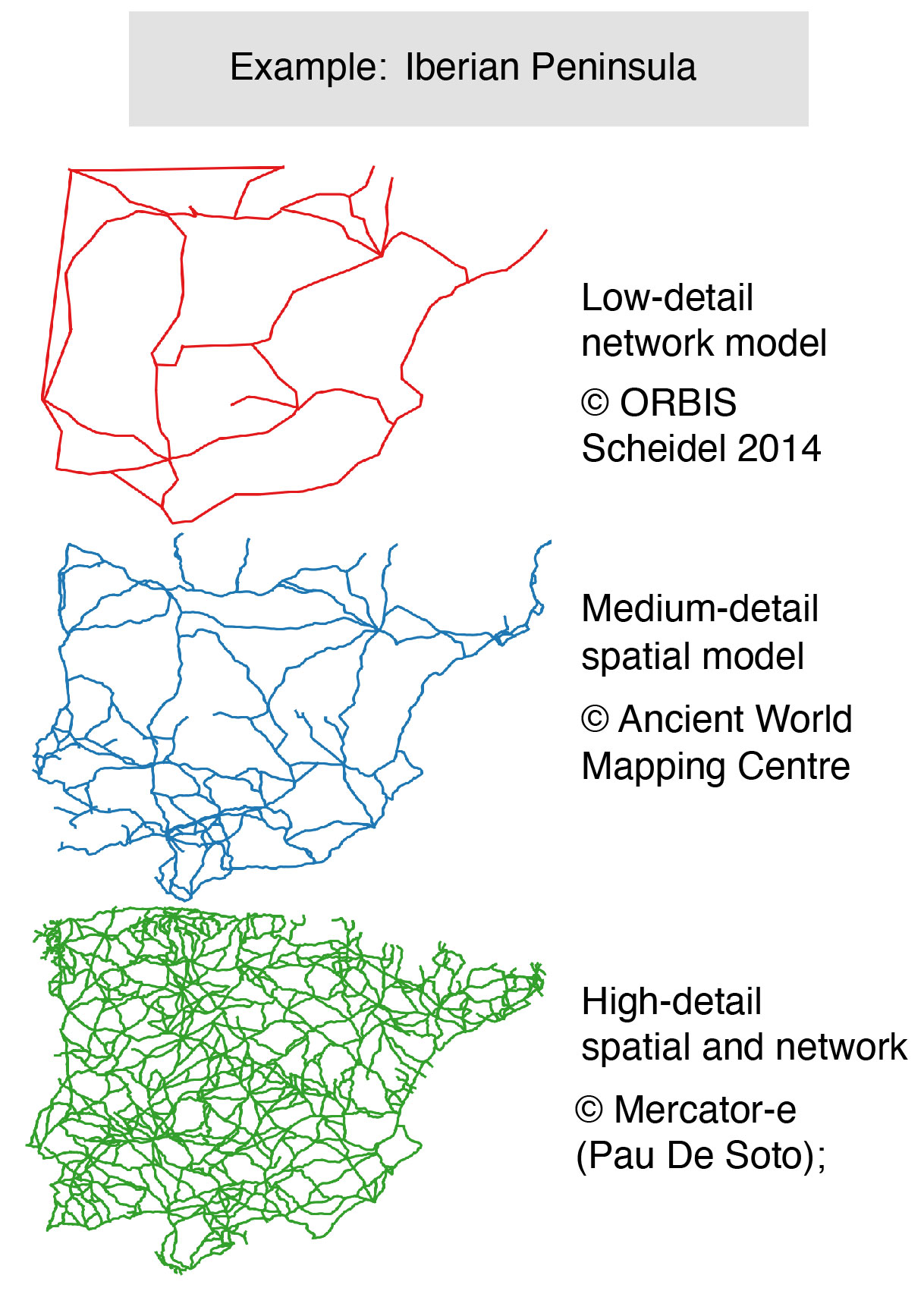

A few digital models for the entire empire do exist, but these are nowhere near representative of what we actually already know about Roman roads (nor do they claim to be). The roads of the Iberian Peninsula in Figure 1 offer a striking example for comparing existing digital models. At the top of Figure 1 we have the ORBIS model, a very useful network representation of the Roman transport system. It was purposefully kept very abstract and low detail because it serves as a tool to study the overall shape of movement through the Roman world. In the middle of Figure 1 we can see the much more detailed spatial tracks of Roman roads captured in the Empire-wide road network available from the Ancient World Mapping Centre. This is currently the most detailed Empire-wide digital representation of Roman roads. These are digitisations of the canonical atlas of the ancient world (the Barrington Atlas), which maps the roads throughout the entire Empire in what seems like very high detail. However, the discrepancy between this source and the amount of detail we get when aggregating published evidence of roads becomes clear from the bottom of Figure 1. Not only do we see far more roads (most of them are minor roads), but we also notice that the actual spatial tracks of these roads are far more detailed.

This example at the bottom of Figure 1 is the result Dr. Pau de Soto’s work in his project MERCATOR-E, where he aggregated available evidence for the Iberian Peninsula. But this kind of work is possible for the entire Roman Empire. The challenge is not to perform the foundational research, it is to digitise and aggregate what is already known.

To support this process, Pau de Soto and I teamed up to develop project Itiner-e (supported by a grant from Pelagios). This is the first gazetteer of ancient roads: a framework where parts of roads can be digitally documented in full detail and uniquely cited, such that this data can be linked with other linked open data.

The work of developing a highly detailed model for the entire Empire is underway. In the meantime, we can already road-test some of our research questions with the useful resources from ORBIS or the Ancient World Mapping Centre. For example: it is often said all roads lead to Rome, but which roads get you there faster?

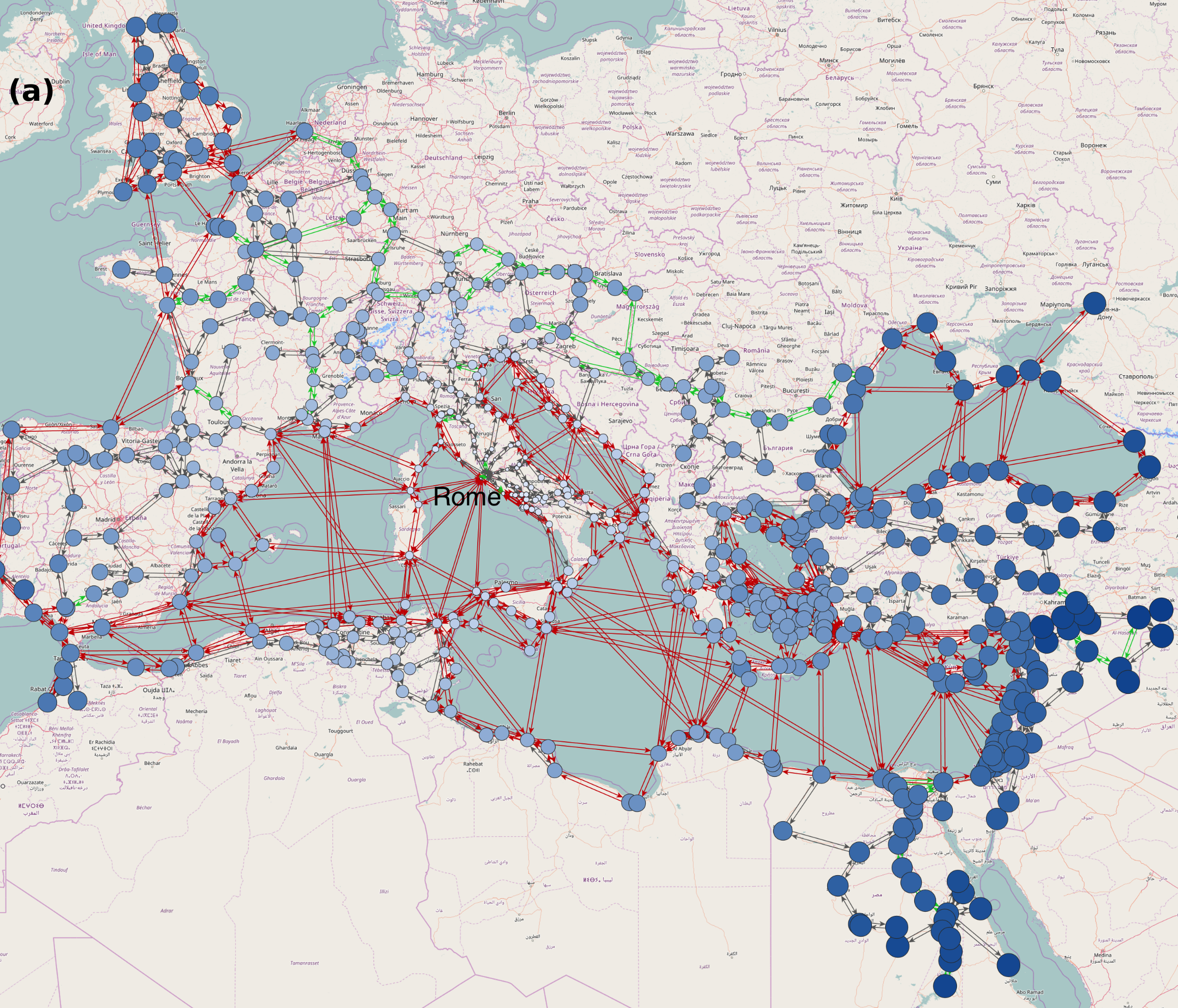

In Figure 2, I have used the ORBIS model to explore this question. Every dot is a city in the Roman Empire, and the lines indicate the ability to move from one city to another over Roman transport links. Grey lines are roads, green lines are navigable rivers, and red lines are sea connections.

The size and colour of the dots represent how close each city is to Rome over the transport system; the larger and darker, the further away from Rome. This is achieved by calculating the fastest route over this network from every city to Rome: a GPS or Google Maps function for the Roman route map.

This geographical representation of the transport network reveals some interesting features. We can see an obvious general trend that the closeness to Rome decreases with as-the-crow-flies distance, even though we used network distance to calculate these results. We notice that much of present-day Tunisia, the region of ancient Carthage, is relatively close to Rome thanks to efficient maritime links. We can also see that the farthest western cities on the British Isles are still closer in network distance than the farthest cities along the Nile, the Black Sea and in Mesopotamia.

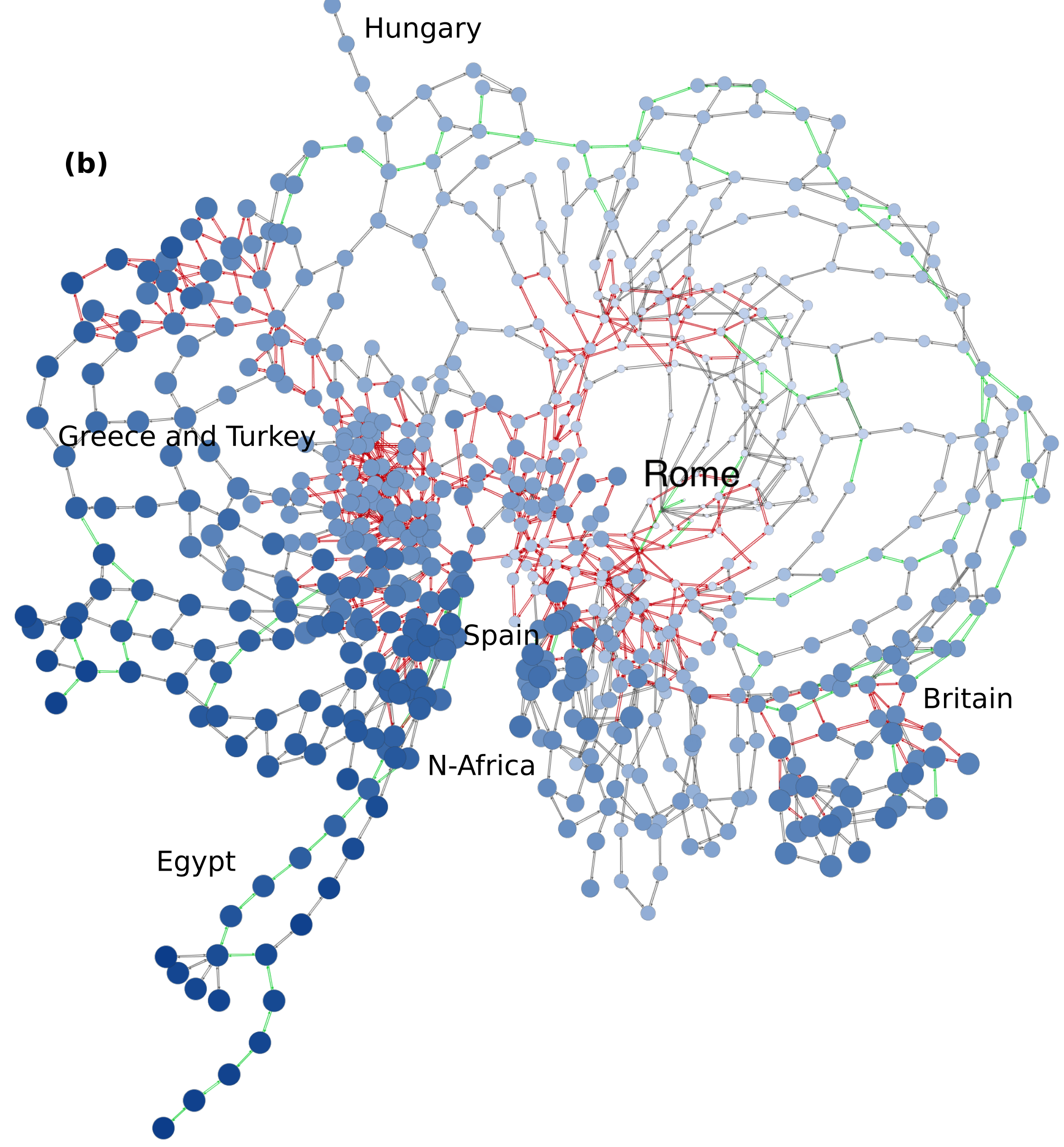

Figure 3 represents this same network in a different way: we have thrown away all geographical locations and the map, and just positioned each dot based on how it is connected to all other dots (a so-called network topological layout). This alternative visualisation highlights different things. Notice how almost all lines at the centre of the picture are sea routes: this network representation reveals that the maritime connections draw all regions’ road networks together, and that they facilitate fast movement throughout the entire transport system.

This is just an abstract example, which highlights the kinds of general insights about Roman transport we can gain thanks to an Empire-wide model such as ORBIS. A more detailed model would allow us not only to derive such results with more accuracy, but also to better understand the role of particular regions’ road structures in giving rise to the Empire-wide patterns. Creating such a high-detail digital model involves a lot of work aggregating existing sources, but it is an entirely doable task. And clearly, such a valuable resource is worth pursuing, which I aim to do over the coming years at UrbNet.

Relevant references

Carreras, C. and De Soto, P. (2013). The roman transport network: A precedent for the integration of the European mobility. Historical Methods 46, 117–33.

Scheidel, W. (2014). The Shape of the Roman World: modelling imperial connectivity. Journal of Roman Archaeology 27, 7–32.

Talbert, R. J. A. 2000. Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World. Princeton: Princeton University Press.