An inaugural lecture on Zoom

Associate Professor Tom Brughmans’ inaugural lecture was held on Tuesday 27 October. Here, Tom Brughmans recalls how two successive lockdowns eventually forced the lecture online, how this had some surprise advantages, and what the talk was about.

By Associated Professor Tom Brughmans.

Academia was different in February 2020: scholars travelled, people met face-to-face, conferences were held, plans were made. I had no reason to doubt this academic reality when I started my associate professorship at UrbNet on 1 February 2020. This was the first embedded tenured position at UrbNet and an inaugural lecture for the post was scheduled for 12 March. This was the day all in-person meetings at Aarhus University were cancelled and Denmark went into lockdown. Academic reality changed from one day to the next, and my inaugural lecture was postponed, what a shock! But surely we would just be in lockdown for a month or so, and then we could give talks again in April or May, right?

As it turned out, it would be slightly longer than that. In-person meetings remained impossible until the summer, and a spike in COVID cases in Aarhus resulted in a short second lockdown in August. But at the end of summer we had every reason to believe we could hold some events again if we followed all necessary restrictions. We rescheduled the event for 27 October in the large and beautiful auditorium of Moesgaard Museum, where social distancing would be easy. Unfortunately, it was not to be. A second wave of infections in Denmark really gathered speed in October, and all in-person events were again impossible from 26 October – a day before my inaugural lecture. Caught on the day of both waves and lockdowns in Denmark: what are the odds?

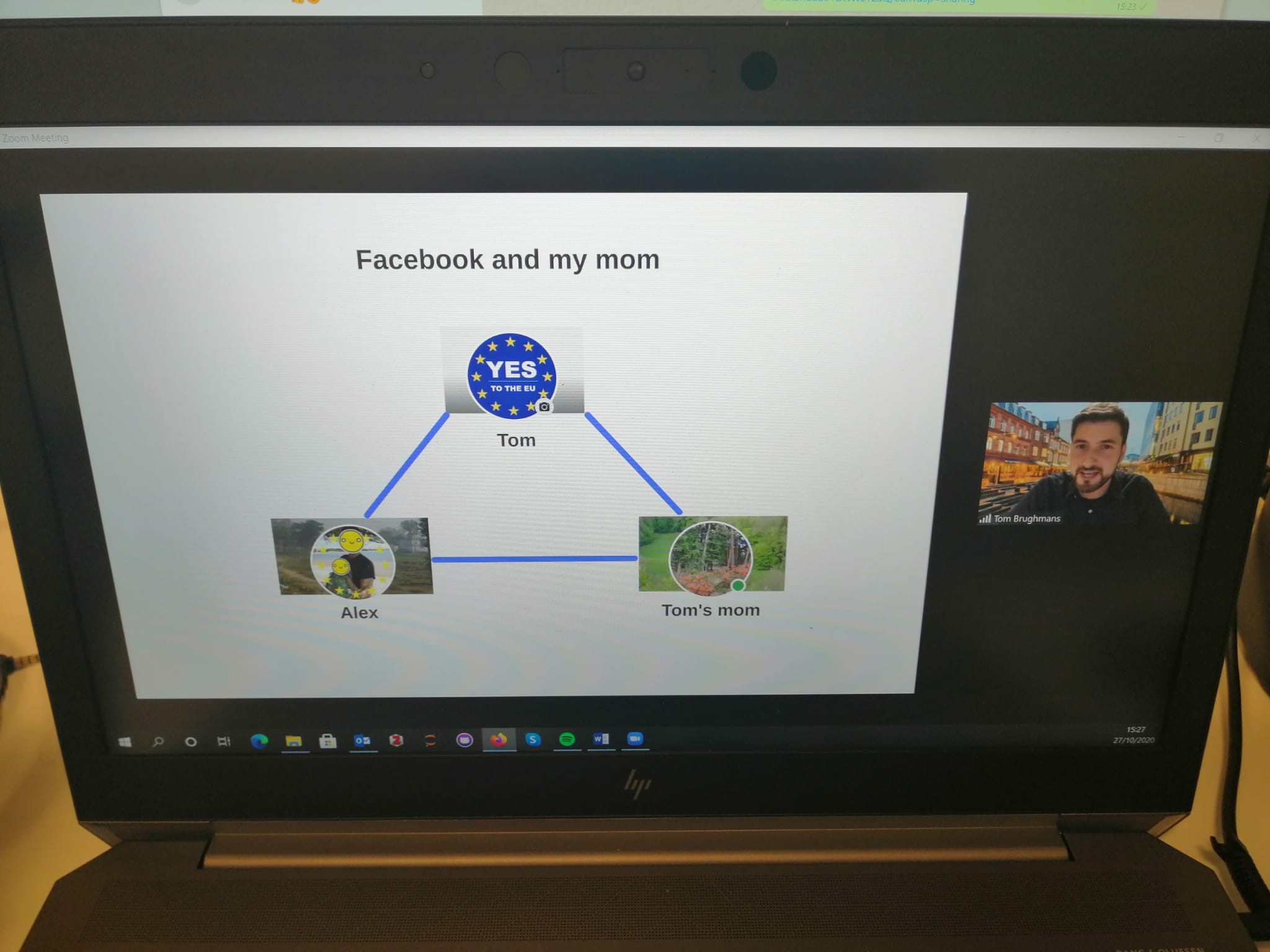

Luckily, we decided to go ahead with the lecture on Zoom instead. It was a bit disappointing I could not share this moment with all my colleagues in person, and it was rather odd to communicate big ideas and make strong statements to a computer screen full of tiled names. However, there was a really lovely advantage to this new format though: way more of my colleagues in Aarhus, Denmark and abroad could follow the lecture than would have otherwise been possible. In essence, I was able to share this moment with a much larger and diverse group of colleagues. A surprise gift I am really happy about. Thanks to all of you who attended the lecture!

So what were those big ideas and strong statements? None other than a definition of archaeological network research, an insistence to make it one of our tools of the trade, and a call to arms for making archaeological network research more ambitious and letting it contribute to our understanding of long-term change in interpersonal relationships.

Archaeological network research can make unique and powerful contributions to archaeology in cases where we formulate theories about how and why relationships mattered in the past. Did the import and export opportunities of three urban settlements change because of the roads that connected them? This is a relational theory! Did new roads get created as a direct desire to change these opportunities? This is also a relational theory!

As archaeologists, we formulate these kinds of relational theories all the time. But rarely do we apply the set of techniques designed to study them: network science. This should not only become common practice, but I would also argue that the potential of archaeological network research can only be achieved if we let our theories drive our network methods. Think through your relational theories, explore what network concepts and techniques are the best representations of these theories, and make archaeological arguments why this theory might be reflected in archaeological data or can be supported/refuted by it. Going through this research process will significantly diversify archaeological network research, and will lead to more interesting contributions to human knowledge.

But how can archaeological network research contribute to a better understanding of our species? That would be through what archaeological data allows us to do that no other network scientists can do: material data allows us to explore how interpersonal relationships between members of our species changed over extremely long time periods. We know social networks were not always the same as they are now. But in what ways were they different, and can this teach us something about our species and its future?

Archaeological network research is a really exciting and thriving subdiscipline, and I cannot think of a more appropriate place to explore its potential than UrbNet. I would like to thank UrbNet’s director Rubina Raja and deputy director Søren M. Sindbæk for encouraging big relational thinking in archaeology, and my colleagues in research and administration for the lovely collaborations. And for organising and listening to my inaugural lecture. If you listened in, I hope you enjoyed it as much as I did.